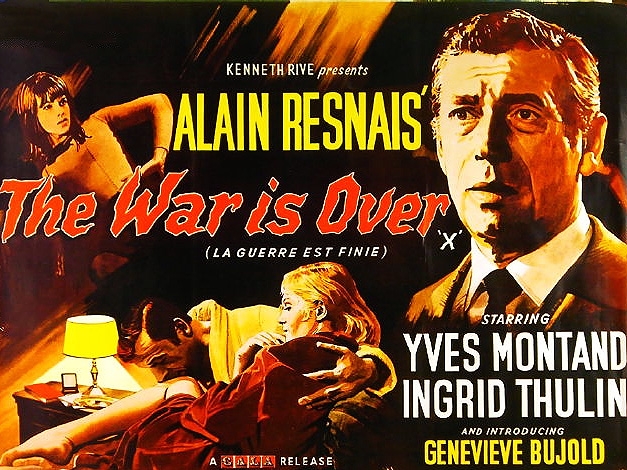

As an adolescent I saw the Alain Resnais film (which in July this year was again projected as a Cannes Classic), where the title was expressed in the affirmative. Its subject was the efforts of an exiled Spanish Republican to continue the struggle from his base in France. Both before and since, the story is familiar. After a Civil war, the losers cannot accept that they were defeated. On the battlefield, maybe. But in their minds, no way. A Civil war is very different from one between separate nations. For in a Civil War, what’s vanquished is your idea of what your country should be – and hardly any of us can reconcile ourselves to that. The salt in the wound, as Resnais admirably demonstrates, is that the new generation which is supposedly “on your side” is also not with you.

In Italy, perhaps even more than elsewhere, public and parliamentary debate over most of the last 2 years has superficially appeared to be mainly about COVID and its consequences. Superficially, because serious political battles have in fact been the real issue. And a lot has happened in that realm. At the beginning of the period, a new coalition government was formed, though with no change to the post of Prime Minister (Presidente del Consiglio, Giuseppe Conte). His position, never very strong, became fatally weakened around the end of last year, and he was replaced, on the initiative of President Matarella, by Mario Draghi. Ostensibly this was characterized as a “technocratic government” formed to cope with the many urgent tasks confronting the country. In reality, of course, though you can have a caretaker government, a technocratic one is an oxymoron. As was to be expected, given his formidable skills and sharp political scent, Draghi has in fact governed with immense skill and firmness.

The shift of power set in train by the events at the top of the pyramid has had many repercussions. Mario Salvini, who had seen himself (and perhaps still does) as the Prime Minister in waiting has been severely disillusioned. Forced to indicate whether he and his party, La Lega, would support Draghi or not, he agreed. But he has constantly prevaricated on individual issues and thereby confused his followers (and, on occasion, himself). Furthermore, several issues regarding financial affairs of his party, behavior of some key lieutenants, and sundry other matters have added to his problems. As I write, his position as leader of the Party is under question. He will probably retain the post, though now he will find out the hard way how to survive in the open when people are continually sniping at you.

In the meantime, Giorgia Meloni, leader of “Fratelli d’Italia (FdI)” has managed to push her party to the top of the polls. Her line has been to “preserve purity” by preaching a strongly nationalist doctrine encapsulated in the phrase “Amore per Italia”. FdI refused to commit to any across the board support for Draghi and claimed it will judge things as they happen. This has allowed it to criticize almost all measures taken and thereby position itself as some kind of spokesperson for those suffering under COVID (which is of course the majority of the population). Forza Italia, the party originally created by Silvo Berlusconi, has in the interim shifted quite markedly towards the center. Now it says, through the voice of Antonio Tajani, a former President of the European Parliament and still an MEP, that it stands for moderate responsible conservatism. It has given Draghi significant backing and has several Ministers in the government. These 3 groups, Lega, FdI, and Forza Italia, purport to make a common front with which they would hope to have a majority in the next general elections, scheduled for 2023 at latest. Increasingly, however, their proclaimed alliance appears fragile and its durability is in question.

In the middle on a right left categorization may be the Five Star Movement. I say “may be” since it is thoroughly unclear what it stands for. At its inception (only a few short years ago), it spoke boldly about not being part of the old style politics. Now it has been fully sucked in, but appears to have no clear stance except the hope of its politicians to stay elected (something which will be tough in the next parliamentary elections since the number of seats will be appreciably fewer due to an electoral law -promoted by the Five Star itself back in the balmy days). As usual, its necessary to focus on individuals. Conte, once removed from the post of President del Consiglio, managed to obtain the title of leader of the movement. He seems to have smoothed over disagreements with Grillo, founder of the movement, but is far from having substantial backing. He tries to present himself as all things to all people, and obviously backs Draghi.

Otherwise, there is little to say. Luigi di Maio has effectively left the movement since he has grasped that it has no future. Given his determination to make a life long go of politics, he has to be careful to avoid conflicts. In the Draghi government he shrewdly negotiated for the post of Foreign Minister. That role offers him three principal advantages. First, he is working with the diplomatic corps, very much the best set of public officials. They can, and do, protect him from blunders due to his lack of knowledge of the field. Second, in any case Draghi is effectively in charge of international affairs so the Foreign Minister can simply keep quiet. Third, by a fortunate turn of the calendar, Italy currently has the Presidency of the G20. Di Maio can thus gain some international exposure at minimal risk. As he works out his political future, he remains in the game while avoiding commitments.

Next we come to the ubiquitous figure of Matteo Renzi. He too has deliberately remained in the background in the period following his staging of the removal of Conte. Instead of engaging significantly with the cut and thrust (more cut than thrust) of politics, he has been busy involving himself with private firms. Very recently he joined both a Saudi enterprise (let’s not forget his visit there around the beginning of the summer) and one with connections in Russia. At the just completed administrative elections in a number of key cities and regions, he claimed credit for helping Enrico Letta to gain the parliamentary seat of Siena. When Renzi was still in the Democratic Party (PD) and Letta was Prime Minister, Renzi played a notable role in unseating him. Subsequently Letta went to Paris, and only recently returned to regain leadership of yet another political grouping (PD) searching for compass points. Hence you may make what you will of Renzi’s Siena sermon. It smacks more of a warning to Letta that his room for progress is still conditioned by what the Florentine decides.

The preceding comments summarize the state of the PD. But Renzi was not the only one to go his own way. Carlo Calenda, another former minister and currently a member of the European Parliament, also created a small political grouping (Azione) in the period under review. He would probably label himself centrist, with a leftish tilt. In the aforementioned administrative elections, he stood as a candidate for the post of Mayor of Rome. He did not, as my American friends would say, make the playoffs (this weekend) but gained a more than respectable share of the votes cast (around 18%). Gualtieri, a former EU official and Minister of Finance under Conte 2, stood as the candidate of a leftish persuasion (though the label is mild, and for some would represent a misleading etiquette), decidedly defeated a candidate of a notably rightist persuasion, Michietti. in the second ballot. Michietti was the handpicked candidate of Meloni. The significant thing here is that Calenda had refused in no uncertain terms to ask his supporters to switch to Gualtieri for the second round of voting, unless the latter explicitly avoided any attempts to woo supporters of the outgoing Mayor, Virginia Raggi (Five Star). Calenda is trying to stake out a political territory where people of the Raggi/Renzi ilk, not to mention all points right, are anathema. In his own way, he probably seems himself as a version of Draghi in terms of seriousness and competence.

It is against this backdrop of individuals, groups and tensions that the events of Saturday 9 October need to be interpreted. Throughout the COVID epidemic, the rightist groups have cloaked themselves in the mantle of defenders of personal and group liberty against those imposing restrictions based on public health grounds. Until the commencement in earnest of mass vaccinations, their message was muted. But in the very recent period, their voices have become strident. The ostensible hot point has been the government decision to require all those returning to work in factories, offices and other locations where numbers of people must operate together, to present at the entry of work places their Green card, showing that they have received the two vaccinations. Failing that, they will be PCR tested (at their own cost). Those failing the test will not be allowed entry and the firms where they work will presumably not pay their salaries. This has inevitably been denounced as a major infringement of personal liberty, as well as a hindrance to economic recovery. Thus the No Vax movement is up in arms and is strongly backed by FdI.

On “sabato nero” a large demonstration to demand that the government retract its measures was organized in Rome. In the course of that demonstration, violence on quite a large scale occurred. Persons belonging to a long existing and avowedly fascist entity, Forza Nuova, were present at the demonstration and very active. The building of the CGIL, the major trade union, was attacked and damaged. The forces of law and order were of course present and engaged with the crowd. To nobody’s surprise, this serious outburst has been given many different slants. The CGIL called for a counter demonstration the following Saturday (16 October), inviting all that support the Italian Constitution’s injunctions prohibiting politically motivated violence to stand up and be counted. In short, a stand for non-violent democracy. The CGIL stance, backed most conspicuously by Letta’s PD though also supported by others including Salvini, who most unusually has called for a general calming of the spirits, clearly sees FdI as behind what occurred. FdI has responded by stating that it is not linked with Forza Nuova, that the troubles were caused by a handful of people, that in such a crisis people’s constitutional right to demonstrate must be upheld, and it has further raised some legitimate questions about the way things were handled by the Ministry of the Interior. Meloni herself was not in Rome, nor even in Italy. She was in Spain invited by the Vox party to give a key speech at a gathering organized in a place dear to Spain’s neo fascists. Judging by the videos, she delivered her harangue in more than respectable Spanish and a tone best described as a call to arms.

Thus the issues which have bedeviled Italy since the advent of Mussolini 100 years ago are as raw today as they have ever been. The head of CGIL, Landini, who in earlier phases of the COVID crisis was himself reluctant to support strong vaccination measures, has not disguised his view that an assault on a trade union building is just what went on in the Mussolini period. The dispute about the events of Black Saturday is in reality a return to the divides of yesteryear.

As I write these lines a major No Green Card at work demonstration which took place in Trieste on 15 October, followed up by later public manifestations there and elsewhere, seem to have failed, at least for now. The announced threat was that, unless the government backed down and allowed people to go to their workplaces, vaccinated or not, there would be a general strike to paralyze the country. Draghi again refused to budge, paralysis did not take hold, and in fact there were record leaps in numbers tested and vaccinated. Positioning by the various political figures mentioned in this article is certainly dictated not so much by any strong beliefs, or even by a sound knowledge of the facts, but more with an eye to a post Draghi government. Some, especially Meloni and Letta, have chosen a high profile with which their presumed electorates can clearly identify. Others prefer to keep much lower visibility, hoping this will allow them to say what is convenient when and if passions are more subdued.

Virtue signaling, or pretending that your actions are dictated by a firm commitment to principle, is certainly not in short supply but should not be confused with the reality of what is happening. Note, by the way, that actual vaccination rates in the forces of law and order are much below the national figure, which may or may not indicate feelings there (to put it bluntly, there may be appreciable support for No Vax in that group). And at the level of politicians themselves, an important member of one political party, a person with a moderate view, had to state when asked what the vaccination rate in the parliamentary chambers is, that they simply did not know.

Resnais’ film was shot, if my visual memory serves me well, in what is best described as black and grey. Somehow those colors seem perfect for the Italian condition today. Is La Guerre enfin finie, ou bien en train de reprendre son haleine ?

Peter O’Brien, 25 October 2021