Issue

Analysis

Conclusions

Issue

Within the past 12 months, it appears as if many changes have taken place in political parties and allegiances in European countries. Is this in fact the case? What do they tell us about how decision making might be made in the future? Are they likely to assist in meeting the democratic challenges the continent faces?

Analysis

There has been a long drawn out electoral period in France. From the effective start in August 2016 to the end this month, the time honored 9 months will have passed. The birth pangs of “le nouveau regime” have been characterized by the twin processes of tearing apart and pulling together. The traditional left and right spent their primaries in fierce civil wars, at the end of which the respective victors made pathetic (and unsuccessful) pleas for rassemblement. Macron came through on the Gaullist message “I am taking the best of the right, of the left, and of the center, and shaping them into one”. Though he has not said so, the President is similarly seeking to blend nationalism with Europeanism. His policy stances are strongly pro-France, but within a relatively open trade and investment environment. His focus on reform within the Eurozone in fact leans heavily on a single budget which would slant spending firmly in directions suitable to France. While he has promised that the notorious “budget deficit” will be reduced over the quinquennat, the reduction will be at a French speed.

The vision of how the democracy will function is clear. A strong Presidential structure, ready to use the institutional devices of the Fifth Republic to drive through changes. A legislative structure to complement the Presidency. A certain distance to be maintained between the State apparatus and the media.

The vision for the economy and society is similarly easy to discern. A liberal economy, with a firm accent on decentralized decision making in the labor market (US or UK models, rather than German or Scandinavian). Significant changes to unemployment and pension rules, designed to put greater pressure on individuals to protect themselves. Strong support for improvements at all levels of education. A commitment to the European Single Market. Social liberalism. A security emphasis, with appropriate support to the police and security forces.

The actual policies to give content to the visions will not, in general, differ that much from numerous ideas put forward, and in some cases tried, by other groups. Where France will change is in the seriousness and urgency committed to the implementation. That will generate tough conflicts. But, as the name says, the challenge is to put “La Republique en Marche”.

The campaign had the virtue of bringing into the public gaze some of the terrible behavior of the ingrained political class, the casta as it is called throughout Europe. It has long been known that France is far behind “best practice” a la Scandinave in this area. As an institutionally closed society, reluctant to learn from others, France has allowed politicians enormous latitude to use public money as they want. From Fillon to Ferrand, the defense is always “I did not infringe the law”. This tone deaf reaction, failing to recognize that what society considers acceptable has to be the yardstick (the law, everywhere, almost always lags behind social mores and is in any case usually deliberately framed to be imprecise), may start to alter with Macron’s opening flagship policy, namely to introduce acceptable moral codes into political life. The three laws through which the policy will be given bite are now under consideration by the government. They are a first step in the essential task of restoring some confidence between the people and the political class.

Italy likewise has seen plenty of tumult, though its outcomes are far less clear. Under constant pressure from Il Movimento 5 Stelle, the political class had to alter. Ex Prime Minister Renzi called a referendum to secure changes in the voting system that would, he hoped, allow him to govern with a clear majority in the Italian lower house, while neutralizing the upper house. He lost that referendum by a large margin in December 2016. In the subsequent six months, he has been striving frantically to regain the Premiership. This personal campaign brought about a split in Renzi’s Partito Democratico, and in recent days tripartite negotiations (Grillo, Berlusconi and Renzi) agreed to support the introduction of a proportional voting system “a la tedesca”. For Renzi, the real objective was to bring forward the general elections scheduled for early 2018. Now, Renzi proposes, they should be held on September 24 (the same date as Germany).

What will all this mean for Italy? A tentative balance does not look favorable. Coalition government will almost certainly be the result. Now there is nothing at all inherently undesirable about coalitions (look at the strong tendencies towards autocratic behavior in the UK, which prides itself on its “first past the post” electoral system). But good coalition government relies on common acceptance of the general good as the glue that binds. That glue does not exist in Italy. In short, there are likely to be strong centrifugal forces that weaken any coalition. Above all, it is doubtful that the two central challenges facing the country will be met. The first is introducing non-corrupt behavior into public life (at all levels, not just the national government and administrations). The second is creating a platform on which the country can use its multiple resources to grow economically and in influence. In reality, those challenges are very similar, mutatis mutandis, to those facing France. Confidence in democracy, confidence in the economy. Both countries have plenty of turmoil, yet the gallic variety might be more constructive.

Elsewhere, the corruption curse continues to strike. Right now, a snap general election in Malta is in effect the response of the Prime Minister to the charges levelled against him and his wife. The Conservative party campaign in the UK election (also snap) is hit by charges against illegal campaign financing in the earlier election (some cases are already proven) as well as a series of well documented cases relating to the current election. In Spain, where the casta/corruption partnership has been under investigation for years (and more than 60 people have been jailed), the existing minority government trundles on despite relentless assault from political groups. The Prime Minister himself has now been called as witness in the scandal. Yet the scandals are not confined to the national level political figures – in Andalucia, and in Cataluna, the problem is rife.

In Ireland, there will be a change of Prime Minister next week since the current PM has resigned due to further corruption issues, this time relating to the police. In the Czech Republic the Prime Minister appears to have lost out in a struggle against the erstwhile Minister of Finance, widely held to be corrupt. The prognoses for the upcoming elections (September) show the ex Minister in the lead. Only in Rumania has the government been prevented from carrying through its manoeuvers, thanks to a combination of superb investigative work by the audit authority and sustained mass demonstrations by the population. If there is one flourishing business where no country or political grouping has a monopoly in Europe, it’s corruption. That’s a field where anti-trust (pardon the pun) measures will never have to be used.

Yet, in the midst of the maelstrom, there are eerie (and exceptionally important) areas where little surface change has so far occurred. Take Greek debt. There the Dijsch (Dijselbloem + Schaeuble) doctrine remains in force. The Eurogroup of Finance Ministers, unofficial but all powerful, continues to dictate terms, and that notwithstanding opposition to the official line within the German Cabinet, and despite the damage the line causes to the overall position of Chancellor Merkel. In Greece, the behavior of both Prime Minister Tsipras and the electorate is puzzling, to say the least. The Prime Minister has held office through an 18 month period in which he has, under external pressure, done exactly the opposite of everything he originally said he would do. Indeed, the welfare of the majority of the people has not ceased to decline relentlessly, and there is no upturn in sight (the financial data and welfare have no correlation in the present context).

In Central Europe, the countries seem mostly to have maintained their political leadership and stances, even when (as in Hungary and Poland) the behavior has been in conflict with supposedly core principles of the EU. Austria looks likely to join the crowd of places that will hold parliamentary elections in the autumn, with Sebastian Kurz appearing to hold a more than decent chance of leading the next coalition.

Conclusions

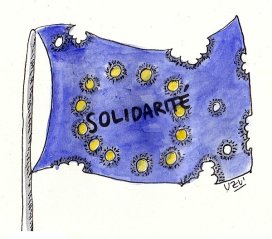

Numerous countries within the EU are going through political upheaval. While so much comment on “populism” has been made, sometimes failing to notice the big differences among such groups in the various countries, less attention has been paid to the seismic shifts within more conventional political formations. Yet is this recomposition, some of it fully visible, the rest still to surface, which is likely to determine the nature of western democracies in the years to come.

The mainstream message in each country is to try and convince the population that “we are all in the same boat”, and that the vast majority of people can benefit from the policies that the newer power constellations are suggesting. To sell that message in a period of very slow economic growth combined with ever fiercer global competition, requires more than a little skill.

Paradoxically perhaps, the democratic crisis in EU countries has been accompanied by ever greater civil society action. To some extent civil society groups, often cross border in scope, have themselves shaped political outcomes, while in other cases they have driven new initiatives somewhat outside the traditional political sphere. What has been labelled “Prafisme” in France explains part, though only part, of the new recomposition. People realize that the usual welfare systems are increasingly vulnerable and provide ever fewer guarantees. One defense is total individualism, another is mixing the individualism with selected collective actions. Politics will ultimately have to adjust to these civil society forces, and recompose itself to complement them.

The struggle against public corruption, like that against terrorism, can never be completely successful. But at least it has started now. The general tendencies are positive. The monitoring comes primarily through the investigative spirit in society, and less so through the law (which often creates the possibilities for corruption rather than raising barriers to it). If European politics can be somewhat cleansed, as well as recomposed, then there are grounds for hope.